September 25, 2006

The reaction to the pope’s recent comments brought back into the limelight the memory of the Mohammed cartoons brouhaha. Back than, much had been written on its potential impact on the free speech. The gist of the argument was, that to limit speech so as to prevent it from offending any group’s sensibilities or beliefs is to kill outright the very notion of free speech. But few specifics were given as to what areas of knowledge might be harmed the most by shying away from depictions of Mohammed.

Here is one: art history. Caricature is an extremely effective tool in the war of ideas, and was widely used in religious debates. During reformation, caricatures of Luther and of popes were widely disseminated, the imagery in both cases being used to equate the opponent with the devil (a caricature of Luther representing him having seven heads – one being a Turk, another a fanatic, the third a rabble-pleaser, etc) is reproduced at number 182 in the recent (1995) catalog of the British Museum’s exhibition of the German Renaissance prints; and we are assured by the accompanying catalog entry that numerous depictions of the pope as the devil’s servant were even more artistically creative.

Now, these images were unquestionably offensive – which is precisely why they were used in the first place – to shock the adversary into reconsidering his views and joining the other side’s position. But should they be excluded from the art history books and debates just because they give offense ?

?

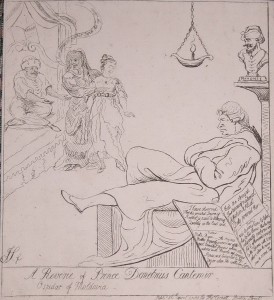

Mohammed cartoons fall into the same category. What do you do about this caricature lampooning Islamic treatment of women – etched by James Sayers (1748-1823) and published in London on April 26, 1788 during the golden age of English caricature – which does contain an image of Mohammed? Do you, in the fashion of Orwell’s 1984, just wipe it out from the annals of art history, or do you treat it as a witness to European attitudes to Moslems at the end of the eighteenth century?

And if there were any illustrated editions of Voltaire’s play “Fanaticism; or, the prophet Mohammed,” first published in 1742 – which just had to have depictions of Mohammed – and not flattering ones at that – what should be done with such books? And there could be a good deal of other and similar art out there. What should art historians do about it?

The answer is very simple, be it art history or not. Even if God actually forbade depicting a prophet, the artists who do so do not at all violate this prohibition – because the problem of the third party forbids us to know who is, and who is not a prophet among those who declare themselves to be such. In depicting Mohammed, an artist shows his idea of not how The Prophet looked, but how a “self-proclaimed prophet” looked, how a “may be or may be not prophet” looked, how a “putative prophet” looked. As a result, the law of not depicting the prophet – if there is such a law indeed – is not at all being broken by those putting on paper their ideas of Mohammed, and there should be no outrage at all when it does happen.